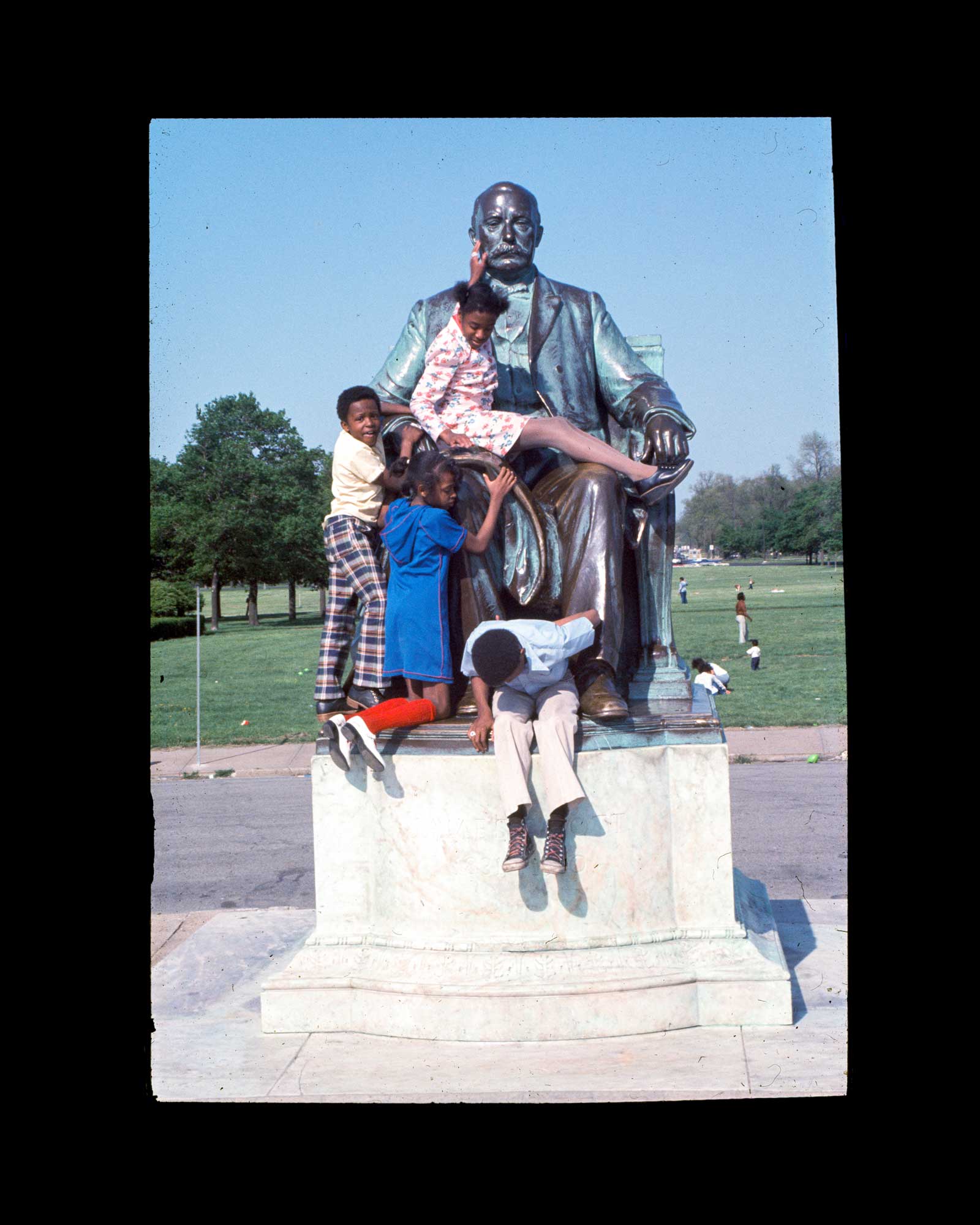

Zora J Murff, From Exceptionalism as a belief system for erasing oneself, 2020. Courtesy of the artist. Commissioned by USFCAM.

The Neighbors: Slide Shows for America

August 24 - November 25, 2020

USF Contemporary Art Museum + Online

ONLINE EXHIBITION

Exhibition Home // Essay by Lisa J. Sutcliffe

Widline Cadet // Guy Greenberg // Curran Hatleberg // Kathya Maria Landeros // Zora J Murff

Curated by Christian Viveros-Fauné, and organized by USF Contemporary Art Museum.

Made possible by Major Sponsor the Stanton Storer Embrace the Arts Foundation, and by grants from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the Florida Department of State.

Familiar Beauty

Lisa J. Sutcliffe

At the onset of the COVID 19 pandemic I took heart in the letter George Saunders sent to his students: “We are (and especially you are) the generation that is going to have to help us make sense of this and recover afterward. What new forms might you invent, to fictionalize an event like this, where all of the drama is happening in private, essentially? Are you keeping records of the e-mails and texts you’re getting, the thoughts you’re having, the way your hearts and minds are reacting to this strange new way of living?"

I thought about the pictures we might be taking (or not taking) as a result of the pandemic. What small acts of poetry and large acts of history must we observe and record? What kind of shifts in perspective might we expect as a result? In the wake of a worldwide examination of structural racism, whose narratives do we most need to see? And in the midst of an economic crisis who can afford to make pictures?

For The Neighbors, Christian Viveros-Fauné invited a group of U.S.-based photographers to offer an interpretation of our moment, of the Americans who might otherwise go unseen. The exhibition’s title suggests a gathering of familiar people, but who are hazily defined; together they make a community, a society, a country. These photographs provide sketches, diaries, and snapshots offering fresh perspectives and providing a richer and more complex depiction of American life. Observing is an important form of listening, of understanding. These sequences of images are an invitation to recognize and appreciate the ways in which a diverse set of hearts and minds have reacted to and reflected upon our common society at this unusual time.

The invitation to photograph unseen Americans inspired Widline Cadet, a Haitian born artist, to look to her own family, many of whom have emigrated and become naturalized citizens. Her pictures memorialize the immigrant experience and mark her awareness of what a family may gain or lose in the process of becoming American. Sensitive to her own lack of historical family snapshots, Cadet began photographing her family five years ago to preserve a record of her generation for the future. At a time when the immigrant experience is vilified for political gain, it is heartening to see personal stories that challenge and disrupt this rhetoric. Many of these pictures could be taken from any family albums—children celebrate in front of a Christmas tree, girls prepare for a night out by applying lipstick—and yet others record the unstructured chaos of family life. The joy of gathering together and constructing a future evident in the overflowing bowls of ripe fruit and vases of bright flowers that set these scenes.

Curran Hatleberg’s pictures are rooted in rural America. He gathers and harvests images of life as it is being lived, finding beauty in the ordinary, much like William Eggleston. Hatleberg captures the peripheral moment, the in-between; not an event but a state of being; not the rainbow, but what happens in front of it. In an era when the majority of images we see are stage-managed for social media, his pictures feel loose, unscripted, not polished or market tested. His pictures of families and groups capture children and the adults they will turn into, pictures of the kind of everyday gatherings that are now out of reach. Though most of the figures gaze out of the frame, a man wearing headphones and filling a gas can regards the photographer with a defiant self-sufficiency. A child gazes into thin air, filled with the thrill of waiting for gravity to return a missive. In the photograph that starts his slideshow an American flag drapes and swaddles a man’s head, as if he is befuddled, his vision obscured by the myth of America, the empty flagpole transformed into his cross to bear. The final picture, however—a photo of three friends brandishing a lit match and a bouquet of wildflowers—suggests a spark of hope, a future we may arrive at together.

New York’s insular Hasidic community drew the attention of Guy Greenberg, who documents life on the street. In his photographs, Greenberg brings us close to his subjects, often at a low elevation, cutting the frame off at the periphery so that the world appears to extend in a chaotic jumble at its edges. This shallow perspective suggests that these pictures offer only a glimpse, just one frame of many dynamic moments in a bustling city. In one photograph two women huddle underneath a packed riser of bleachers. Their heads, brightly decorated with scarves, find comfort together against a sea of black pants and shoes, revealing the true strength of community bonds. Many of the pictures focus on children, their outfits, uniforms, and costumes. Greenberg’s pictures breathe life into the magical world they create from their imagination and the games that take shape on the streets.

Kathya Landeros’ photographs describe a landscape, a place, an agriculture, a system. She focuses on the in-between spaces where suburbs and farmland disentangle from one another. Fences delineate the land within the pictures, serving as boundaries, as canvases for decoration, as a reminder that we are outsiders in this narrative, spying on another life, a child’s game. In other pictures people present what they are growing, in a garden, a community, a neighborhood, a culture, all etched within the golden light and crystal clear Western air. A young woman wears a snake around her arm like a bangle, a modern day priestess offering us passage into the garden. One of Landeros’ final images evokes an iconic picture made by Henri Cartier Bresson in 1938 of two couples picnicking on the banks of the Marne, a photograph that highlights the modern pleasures to be had in this everyday social ritual. Landeros’ Eden is right here, in our backyards, where we make our homes and where there is bounty if we look for it.

The American flag acts as a motif throughout the sequence of photographs presented by Zora J Murff. It appears through a scrim of trees like a symbol we hope to reach—a reminder that democracy is something to strive toward, to achieve through daily practice. Interspersed throughout the sequence are vintage snapshots of the daily life of an African American family, portraits, a construction site dappled by light, a hand reaching through a flowering bush. Blurred found photographs that evoke the passage of time are followed by crisp portraits grounded in this moment. In one image, children crowd the lap of Detroit’s James Scott memorial fountain. In the wake of a summer of protests in which monuments and the histories and legacies they memorialize were called into question and toppled, this photograph suggests a recalibration of the interpretation of our own histories and the pictures we made to memorialize them.

Would those children sit in that lap now? What do our family pictures tell us about the country in which we were raised, and the ideals and myths we carry with us?

Lisa J. Sutcliffe Instagram: @lisajsutcliffe

Follow us to receive the latest on The Neighbors

#usfcam #irausf #artcanhelp #stayhome